Researchers optimize genetic tests for diverse populations to tackle health disparities

Improved genetic tests more accurately assess disease risk regardless of genetic ancestry.

To prevent an emerging genomic technology from contributing to health disparities, a scientific team funded by the National Institutes of Health has devised new ways to improve a genetic testing method called a polygenic risk score. Since polygenic risk scores have not been effective for all populations, the researchers recalibrated these genetic tests using ancestrally diverse genomic data. As reported in Nature Medicine, the optimized tests provide a more accurate assessment of disease risk across diverse populations.

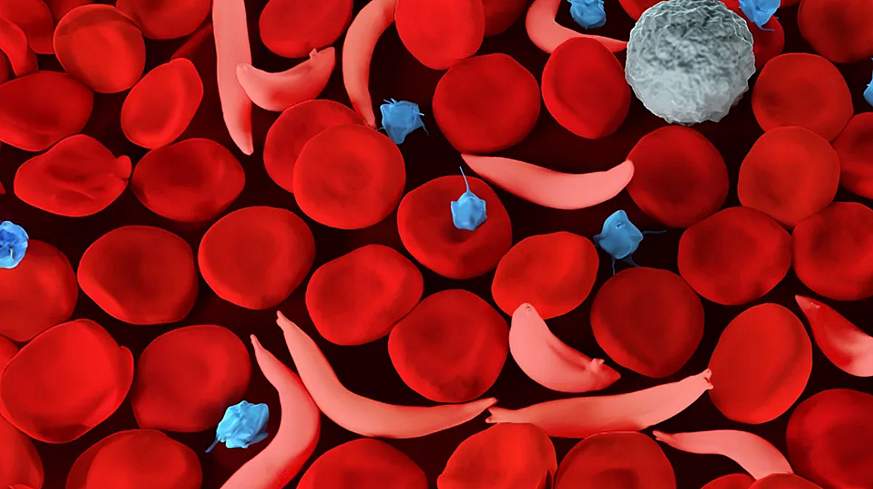

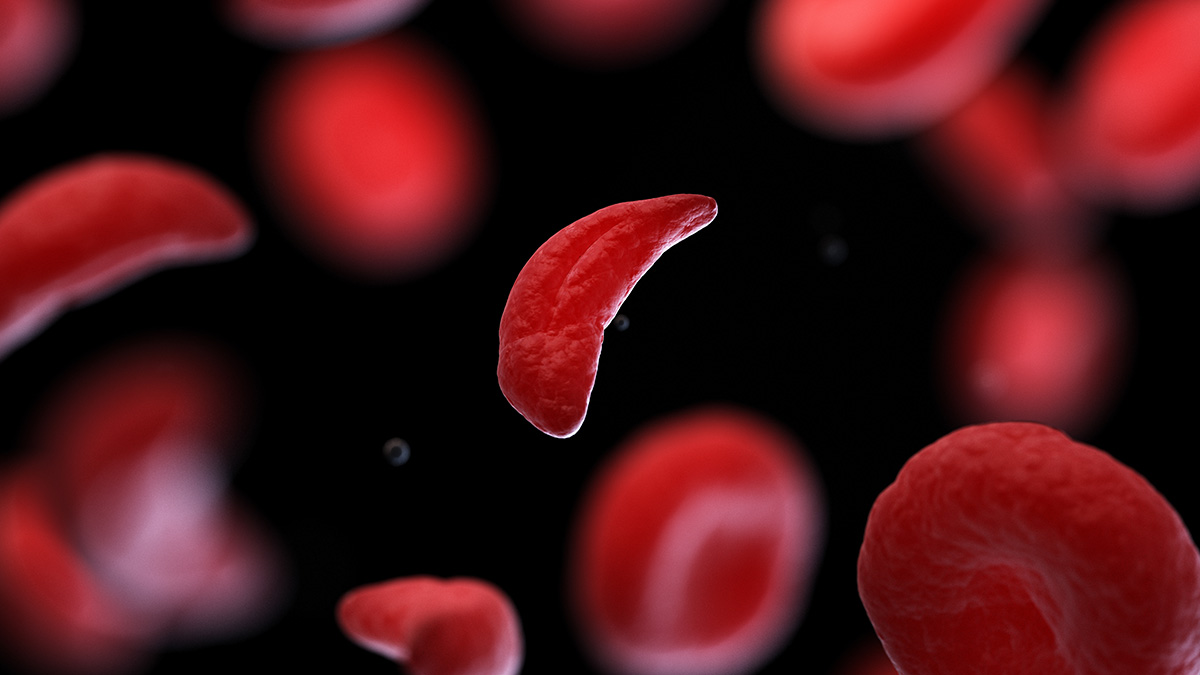

Genetic tests look at the small differences between individuals’ genomes, known as genomic variants, and polygenic risk scores are tools for assessing many genomic variants across the genome to determine a person’s risk for disease. As the use of polygenic risk scores grows, one major concern is that the genomic datasets used to calculate the scores often heavily overrepresent people of European ancestry.

“Recently, more and more studies incorporate multi-ancestry genomic data into the development of polygenic risk scores,” said Niall Lennon, Ph.D., a scientist at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts and first author of the publication. “However, there are still gaps in genetic ancestral representation in many scores that have been developed to date.”

These “gaps” or missing data can cause false results, where a person could be at high risk for a disease but not receive a high-risk score because their genomic variants are not represented. Although health disparities often stem from systemic discrimination, not genetics, these false results are a way that inequitable genetic tools can exacerbate existing health disparities.

In the new study, the researchers improved existing polygenic risk scores using health records and ancestrally diverse genomic data from the All of Us Research Program, an NIH-funded initiative to collect health data from over a million people from diverse backgrounds.

The All of Us dataset represented about three times as many individuals of non-European ancestry compared to other major datasets previously used for calculating polygenic risk scores. It also included eight times as many individuals with ancestry spanning two or more global populations. Strong representation of these individuals is key as they are more likely than other groups to receive misleading results from polygenic risk scores.

The researchers selected polygenic risk scores for 10 common health conditions, including breast cancer, prostate cancer, chronic kidney disease, coronary heart disease, asthma and diabetes. Polygenic risk scores are particularly useful for assessing risk for conditions that result from a combination of several genetic factors, as is the case for the 10 conditions selected. Many of these health conditions are also associated with health disparities.

The researchers assembled ancestrally diverse cohorts from the All of Us data, including individuals with and without each disease. The genomic variants represented in these cohorts allowed the researchers to recalibrate the polygenic risk scores for individuals of non-European ancestry.

With the optimized scores, the researchers analyzed disease risk for an ancestrally diverse group of 2,500 individuals. About 1 in 5 participants were found to be at high risk for at least one of the 10 diseases.

Most importantly, these participants ranged widely in their ancestral backgrounds, showing that the recalibrated polygenic risk scores are not skewed towards people of European ancestry and are effective for all populations.

“Our model strongly increases the likelihood that a person in the high-risk end of the distribution should receive a high-risk result regardless of their genetic ancestry,” said Dr. Lennon. “The diversity of the All of Us dataset was critical for our ability to do this.”

However, these optimized scores cannot address health disparities alone. “Polygenic risk score results are only useful to patients who can take action to prevent disease or catch it early, and people with less access to healthcare will also struggle to get the recommended follow-up activities, such as more frequent screenings,” said Dr. Lennon.

Still, this work is an important step towards routine use of polygenic risk scores in the clinic to benefit all people. The 2,500 participants in this study represent just an initial look at the improved polygenic risk scores. NIH’s Electronic Medical Health Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network will continue this research by enrolling a total of 25,000 participants from ancestrally diverse populations in the study’s next phase.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health®

Post Comment